Richard Cunningham

Richard attributed credit to his mother, Ellen Richardson, for his love of learning early in life, and that there was a correct way to do every job. Richard's mother was sold with her husband and other children. Richard remained on the plantation until Emancipation Proclamation, about three years later.

As a boy, it was Richard's duty to take his master's children to school on horseback. He never had a chance to look in a book, but the hunger for education grew in him. When the Civil War broke out, Richard ran off and attempted to join the Army. They wouldn't take him, saying he had flat feet. Richard was a hard worker, and he held numerous jobs at the brewery and as a farm laborer, which included grain cradling.

He met and married a girl in Louisville who became pregnant and died in childbirth, leaving him with a daughter, Anna. He left the baby with her mother's family and crossed over the state line, into Indiana. His desire for education was so strong that he went to school and sat beside small children until he learned the 3 R's.

Richard and Mary Finley Reed met, fell in love and married in the Wright's home on December 27, 1877. They went to live in Cottage Grove, Union County, Indiana, where his half brother, George Richardson, lived. Richard and George had the same mother, Ellen, but were fathered by two different men. After the Emancipation, they were required to use the last names of the men who fathered them. Richard's father was Cunningham, a wool spinner and plantation overseer. He had forcibly sexually molested Ellen. When Ellen, her husband, and family were sold, Richard was kept on the plantation. But, moving forward, Richard and George were each employed in a tile and brick factory. Here a daughter, Martha Elizabeth Cunningham, and two sons, Joseph Alexander and George Finley Cunningham were born.

One day a man came to buy tile for his place in Howard County, Indiana. It was a new section just being reclaimed from the woods, and they needed a lot of tile. He finally persuaded Richard that he should go there and set up his own tile business. In 1884 they moved into a log cabin on ten acres of ground, southwest of Kokomo, near New London. It was only three miles from the railroad station in Russiaville, but the woods gave the feeling of isolation. Later, when the Federal Government was relocating the Indian Tribes in the Oklahoma Territory, Mary Finley Reed Cunningham would have been eligible to go, since her grandmother Gomer's mother was a Cherokee squaw. She felt that this place was wilderness enough.

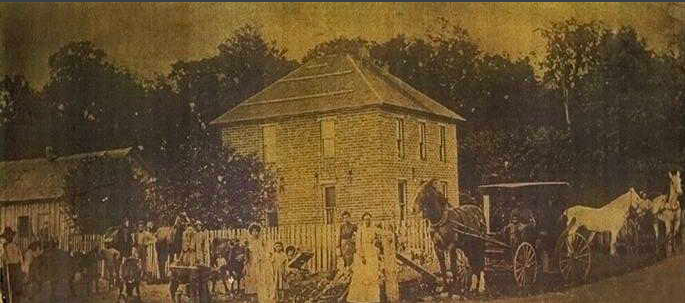

Cunningham Family Farm

In spite of the hardships, she (Mary Finley Reed Cunningham) never became careless or slipshod in her housekeeping. She continued to keep her immaculate home until three days before she died, at age 84. Her beds had long white counterpanes and hand-embroidered pillow shams, spread neatly over the feather ticks, hiding the trundle-beds that were pushed under the big beds in the daytime. Each family member had three sets of clothes. School clothes were taken off before doing chores, and there was always a "Sunday best"' Mary Cunningham seldom went to town when the children were small.

On Saturdays, Richard would hitch up the wagon and do all the trading. In the spring of the year, he would buy bolts of muslin, gingham, and calico plus denim for overalls and ticking. The feathers were put into new ticking, and the old ticks washed and filled with straw, which was cooler for summer. All shirts and underwear were made at home; muslin for summer and canton flannel for winter. All scraps from the sewing were saved and made into quilts. As soon as the summer sewing was finished, it was time to start on the wool serge's. None of the boys had a store-bought suit before he graduated. The girls had serge dresses. The wool scraps were made into comfort tops and lined with outing flannel. Then there were white flannels for the babies plus hand-sewn dresses and bonnets.

Nine more children were born in New London, Indiana: Lulu Belle, William Harison, John Edmond, Myrtle May, the next died without a name, Ira Sylvester, Landon, Eva Marie, and Clarence McKinley Cunningham.

In addition to their (Richard and Mary Finley-Reed Cunningham) own growing family, they boarded the "hands." This meant four to six more hungry men every day at noon. These men lived in New London, including Richard's half-brother, George Richardson. Richard and George sent for their mother, Ellen Richardson, but she was dissatisfied and did not stay. George's wife was named Millie, and they lived at the top of the hill with their two sons' Bush and Willie. Aunt Millie would lend a hand with sewing, and she always had new mittens for the Cunningham children when they came for Christmas dinner.

Another of the hands was Theodore Duggard. He and his wife had two daughters, Hazel and Ineatia. There was Charlie Harper, whose wife was Jennie, and Mr. and Mrs. Will Curtleyand their sons Floyd and Lloyd. There were also the Webbs who ran the sawmill behind the tile shed.

To get to school the children went to the back of the lot, over the fence, and through another farm to the North Road. This was School District #6; a red brick building where all eight grades were taught in one room. In the wintertime, the snow would sometimes be so deep that the fence would be indistinguishable. On those days Richard Cunningham would go first and break the path, followed closely by Charles (Charlie) Reed, Jr., Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham and Joseph (Joe) Alexander Cunningham. In the spring the cow would follow them as far as the fence and stay nearby until they came back. Then she would follow them back to the house to be milked. They also kept plenty of chickens so there would be enough eggs for the table and some for trading. Their eggs and chickens always brought the top price. As the woods were cleared, they were replaced by a garden. Later an orchard was added. When the girls were older, berry bushes were set out. What they gathered over their own need they sold in Kokomo for pin money.

The year George Finley Cunningham was five, Mary Cunningham was going to keep Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) out of school, but the teacher let George come too, thereby he became the first one-man kindergartner in the district. The following year under regular discipline, he developed a dislike for school and dropped out when he was older.

On Sundays, they would put fresh straw and quilts into the wagon, and they would all pile in to go to church. During the winter the wagon wheels were replaced by runners. They worshiped in New London at the Friends Meeting House. The family burial plot is in this churchyard. Later they joined the Church of the Brethren which was on North Road, near No. 6 School House. New London was the older settlement, but it was by-passed by the railroad, so Russiaville became the Post Office and Trading Center. There are still buildings there made of Cunningham brick.

During the Panic of 1889, Richard Cunningham not wanting to lay off his hands carried them on credit and made bricks for his own barn. Mary Cunningham was so disappointed that he built the barn before the house that he got a horse and buggy for her (Mary) own use. She did not have to wait for the wagon anymore. In the summer of 1891, when Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) was twelve years old, she took her sister Lulu Belle in the buggy to do an errand in New London. The hold-back strap was not properly secured, and the horse ran away. The buggy tipped over at the turn, and Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) broke her arm. Her father held her while the doctor set it and applied a cast made of wet paper.

Charles (Charley) Reed Jr. never finished school. He was only seventeen years old when he married Sophia Woods but never moved out of the community. He settled in New London and became a contractor of house-moving and foundation work, using mules because they were stronger than horses.

Marth Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham lost a year of school because of her eyes, so she and Joe graduated together, then went together to Dunkard College at North Manchester, Indiana and graduated in 1903.

Joseph (Joe) Alexander Cunningham took a liberal arts course and moved to Chicago. Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham took Bible training and was sent as a missionary to Palestine, Arkansas. She taught school and conducted church services.

About this time Richard and Mary Cunningham built a house. It was a four-square house, like Mary's favorite hymn' of Georgian architecture. On the north side of the road, facing south, it was centered in the lot with a garden to the east and the tile yard to the west. Two reinforcing rods went all the way through from front to back between the upper and lower floors with iron stairs at each end. The front door was in the middle of the house with a cement walk leading out to the road and another walk around the west side.

The two east rooms downstairs were bedrooms, the spare-room in the front and the master bedroom in the back. Facing the front door was a closet that extended back under the stairway. The living and dining rooms were connected by an archway that was draped with beading. The kitchen wing extended from the east wall to halfway across the dining room and was a half-step down. North of the kitchen was a storage cellar. This room was excavated about three feet and then enclosed in a double brick wall with a dead air space between, like a thermos bottle. One wall was filled with fruit jars, with a section reserved for tithes. Every tenth jar was saved for charitable donations. There was a set of bins for the root vegetables, racks for the barrels, and a stone ledge for the dairy crocks. The open stairway went straight up, filling the east wall of the dining room, except the doorway to the bedroom. From the landing to the east was the girls' side and to the west was the boys' side. At the end of the hall and over, the stairs was another small room that was called a bathroom but was used mostly for storage.

The kitchen door opened onto a cement porch on the west. A brick walk led across the yard to the driveway. North of this walk was a pump and a deep drilled well. Water from this well was always cool and abundant. Behind the pump and marking the boundary of the yard was a smokehouse, a wooden shed used for curing meat at butchering time. It had an extended roof at the end near the house, making a sort of covered passageway.

Behind the smokehouse was the chicken-yard. The old ones were all over the place, but the young ones were fed here. From there back to the barn was a low place that had been dug out before and was now refilled with stones and broken tile. The main entrance to the barn was to the west. The center aisle was big enough for a load of hay. The stalls were on the south side with a box stall in front. The grain bins were north of the aisle, and the haymow was on both sides.

The Church of the Brethren was initially called German Baptist, being founded by the Pennsylvania Dutch. They were nicknamed Dunkards. Nellie joined the church in Pennsylvania. She was later brought to Indiana to visit. She stayed at the Cunningham's a year and then went to Mt. Morris where there was another college, before coming to Chicago. She married Andrew Rainey who had come to Chicago to attend Bethany Bible School, another Dunkard College. He left school and got a job at the Palmer House.

Willie Newton Dolby joined the church in Ohio and met Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) when she was doing evangelistic after giving up her charge in Arkansas. They were married in 1907, at her home with hundreds of guests. He was employed as an engineer at Wilberforce. She finished her Greek and was ordained into the ministry while they lived there.

In 1908 Joseph (Joe) Alexander Cunningham married Blanche Radcliff of Frankfort, Indiana and took her to Chicago. He was working as a meat inspector for the Health Department. He went to medical school and became a doctor while raising his family.

George Finley Cunningham married Flora Stewart in Muncie, Indiana.

Landon died of pneumonia at the age of thirteen.

Myrtle May Cunningham wanted to marry in June, but her mother (Mary Cunningham) persuaded her to wait another year. Her husband was Fred Robbins. She (Myrtle May) died in childbirth a year later.

Lulu Bell Cunningham contracted typhoid and died in 1913 during an epidemic in the community while helping out some of the neighbors.

The Cunningham's were friendly with the ministers of the black churches in Kokomo and surrounding towns, but one of their favorites was the Rev. Pettiford of the A.M.E. church. He had three daughters, Ella, Myrtle, and Lila. After his promotion to Presiding Elder, he settled in Terre Haute so that Myrtle could attend college there. Myrtle Pettiford was in her first year when Rev. Pettiford died. She (Myrtle Pettiford) then married William (Will) Harrison Cunningham in 1914. William attended school in Terre Haute and got his teaching certificate. However, since his father needed him, he moved to Kokomo and commuted to the tile yard.

1917 was the last year Richard Cunningham operated the tile yard. A description of the operation follows:

The front part of the lot west of the driveway was a vacant space where the cabin had stood. It was now used as a turn-around and loading zone for the wagons that came to get tile. The finished tile was piled here until called for use. The first building was the kiln made of brick and shaped like an igloo with fire pits at intervals around it. The doorway was north, facing the shed.

The shed was a large two-story frame structure, perhaps thirty feet wide and three times as long. It had a large front door that slid back to expose both floors. About mid-way on the side by the drive was a tramway. This was an embankment covered by a gangplank arrangement with a platform on top. The horses pulled a load of clay up to this ramp, and the clay was unloaded through an opening in the wall into a bin. The horses were then driven down the front of the ramp and back to the pond to get another load. One could go up the ramp and look through the opening to watch the operation.

A series of small scoops on a chain drive would carry the clay up to the top of the hopper and dump it in. The stones would be ejected, and the clay was kneaded to a proper consistency, water being added if necessary. Then it was forced through a mold, which could be changed for different sized tile or brick. It came out on a conveyor belt table about six feet long. There was a wire on a guillotine attachment that cut it to the proper length. It was picked up from the table by hand and passed overhead to the floor above. It was then placed on a hand truck and taken to the drying shelf. All the space in the shed, except the machine room, was taken up by tiers of shelves. After the tiles were thoroughly dried, they were tossed out and caught by a man below and placed in the kiln for baking. When the fires were started in the pits, Richard slept on a cot in the shed so he could keep them going all night. There was another day of cooling before they could be removed. North of the tile shed was the sawmill. It was fascinating to watch the big whirling blade cut into the logs.

Northeast of the barn was the orchard. West of the orchard was the pond where the current digging was going on. Richard bred some good horses. He kept two teams of draft horses and a carriage horse. In addition to the buggy, he had a fringed-top surrey and a spring wagon for light hauling. The boys had to have their own rigs to go "sparking' *(courting) in.

When Charles (Charlie) Reed, Jr. mechanized his business, he needed more room, so he bought a farm east of New London. His children were John, Fern, Cecil, Russel, Virgil (who died in infancy), the twins, Earl and Pearl, and Mildred. John served in World War I.

They were not drafting farmers, so John Cunningham and Ira Cunningham rented a 210-acre farm in Robert's Settlement in Hamilton County. This was a land-grant section, most of which was still in the hands of the descendants of the original owners. The farm belonged to the wife of Rev. J.P. Wallace who had been born there. The boys persuaded their sister Eva Marie Cunningham to keep house for them. She had studied music at Mt. Morris College so they bought her a piano and she started giving music lessons. Ira Cunningham had attended Bethany Bible School before moving here. He married Bessie Smith of Marion. John Cunningham married Francie Roper of Noblesville. Then Ira Cunningham moved down the road to the Jim Rice farm, and George and Flora Cunningham moved into the tenant house. They had five boys: Richard, William, John, Lewis, and Ira.

After the war, John Cunningham moved to Noblesville, and their father turned over the operation of the tile yard to William (Will) Harrison Cunningham and moved to the farm. Clarence McKinley Cunningham had just graduated from New London high school, being the eighth member of the family to make it.

After five years at Wilberforce, Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham lived one year in Kokomo and four years in Mt. Morris before moving to Urbana where they (Wiley) Newton and Martha Cunningham Dolby bought a home. She and Wiley Newton had six children: Richard, Margaret, Theodore, Alta, Elizabeth and Lulu May.

In 1919 a reunion was held at the farm. Joseph (Joe)and Blanche Cunningham came with their four, Kathleen, Wilbur, Robert and George. Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham came with her six. William (Will) and Myrtle Cunningham had two, Donald and Stella. Clarence Cunningham and Charles (Charlie Reed came up for the day from New London. Everyone was there but Eva Cunningham. She had gone on tour as an accompanist with the Reverend Roberts, the evangelist.

An important part of life at the Cunningham's was the family prayers. While the men were doing the chores, the girls would help their mother get breakfast. Everybody would assemble in the living room while their father read the Scripture Lesson. Then they would kneel while father or mother would lead a prayer. After that, they would go to the table for breakfast.

Ira Cunningham left the Rice farm and moved to New London to help William (Will), Cunningham. Ira Cunningham and Bessie had two children, Mary Delight and Allen. Clarence Cunningham was the only one in the family who joined the Friends' Church. He matriculated at the Quaker College of Earlham in Richmond, Indiana. After his graduation, he was elected delegate to the International Youth Conference in Europe. He saw Aunt Eleanor Alexander in Paris while she was on tour at the same time. He returned to Richmond and married Elizabeth Burton who was living there with her Aunt Mary Finley Reed. She had been born in Marion, but her parents were dead. Clarence Cunningham had majored in Social Science and took a job in Zanesville, Ohio.

The tile business ceased to be profitable, so William (Will) Cunningham closed it down and moved to Chicago where he entered the Railway Mail Service and bought a home in the Englewood section. Richard and Mary moved back to the tile yard and stayed alone except for occasional visits. Ira Cunningham went to work in Richmond where his health failed, but he was here off and on until his death in 1927. In 1926 Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham and the children came for a visit, but after only four days they were called home by the news that Wiley Newton Dolby had died of a heart attack.

A reunion was called in August of 1926, but Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) did not get back. William (Will) Finley was there from Detroit with his children, Clarence and Eva Finley. Joseph (Joe) and William (Will) Cunningham came from Chicago. That same year Earl Reed died. Clarence and Elizabeth Cunningham left Zanesville and moved to Chicago.

The Golden Anniversary was Christmas of 1927. Joseph (Joe) came alone because Blanche was ill. Clarence William and William (Will) Cunningham with Ira Cunningham's children were in an automobile accident, but no one was hurt. Eva Cunningham had married Alonzo Avery, and she was there with her son Bobby.

John Edmond Cunningham was divorced from Frankie Roper Cunningham, and he and George Finley Cunningham were farming the Lindley place on the Range Line, not far from Robert's Settlement. George Finley Cunningham's wife, Flora Stewart-Cunningham died in February, so George and his boys moved to another farm and Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham, with her family, moved in to keep house for John Edmond Cunningham. The following year, together, they moved to the Wallace farm. Most of the Roberts of the settlement were gone by now but returned for family reunions on July 4 in the churchyard. One of the Robert's boys became a dentist and established a practice in Indianapolis, married Myrtle's sister, Lila Pettiford, and they had a daughter named Doris.

Richard Cunningham died in January 1933, at the age of 84, after a lingering illness. Eva Cunningham took Will Cunningham's apartment and brought her mother (Martha Gomer-Finley to Chicago for the winter. Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham also moved to Chicago. John Edmond Cunningham married Bessie, she and the children went to the farm. George Finley Cunningham married Mrs. Bertha Bradley and moved to the tile yard. their mother (Mary Finley-Reed-Cunningham went back there for the summer. Will Cunningham and Myrtle had another daughter, Shirley. Clarence Cunningham and Elizabeth adopted a little girl, Grace, and then had a daughter, Barbara. They persuaded Mother (Mary Finley-Reed-Cunningham) to live with them.

In 1941, we lost our beloved Blanche Radcliffe-Cunningham who had been the Chicago 'mother' to the whole family. Everyone who stayed in the city went first to their house before they got settled. Her home was the gathering place for many happy occasions.

When World War ll broke out, several of Mary Finley-Reed-Cunningham's grandsons had to go. They all came to see her on their furloughs before they shipped out. She had sold the home-place but was pleased when Will Cunningham repurchased it. In December 1943 after a three-day illness, she died. On a bitterly cold day in New London, she was laid to rest in the Quaker Churchyard. Charles Reed Jr. died a month later.

John Cunningham and Bessie gave up farming and moved to Detroit. He worked as a streetcar conductor for a while and then went into the insurance business.

Clarence and Elizabeth Cunningham moved to Michigan for a while, then out to Berkeley, California.

Joe Cunningham married Mrs. Essie Mae Sharpe and bought a home on Lafayette Avenue.

In 1948 Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham Dolby was ordained a Minister in the Church of God and started holding services in her home. The congregation grew, and they bought an old house which they remodeled, fixing her an apartment upstairs. In 1951 she was injured in an automobile accident.

Sophia Reed died in 1949. Eva Cunningham was killed in a car accident in Chicago in 1952.

The following year John Edmond Cunningham went to Indianapolis to visit Mary Delight and died while there. He was buried at Roberts' Chapel.

Will had a heart attack in 1954 and had to retire. The following January he had another attack which proved fatal.

In 1956 Martha Elizabeth (Mattie) Cunningham Dolby underwent radical surgery for the second time since her car accident. She was up and around during the summer but died in October.

That winter, both Joe Cunningham and George Cunningham had strokes. Both Joe and George had repeated heart attacks. They lived another year. Joe died in November 1957; George a month later and was buried in the Quaker Churchyard.

Clarence Cunningham was the only one left of his generation.

The bulk of the past information was written by The History Committee consisting of Margaret Dolby Williams, Kathleen Cunningham Williams, and Myrtle Pettiford Cunningham in June 1958. All the grandchildren living in Chicago got their heads together and made plans for a reunion to be held on the third Saturday in July 1958, at the home of Frank and Kathleen Williams, in the suburb of Markham on their spacious lawn. At the gathering, plans were made for other reunions.